This article appeared in the July 1988 issue of Jems Magazine.

Kate Dernocoeur has sometimes used the pseudonym Syd Canan

Paramedics were called on a "sick case.'' They arrived at a low-income tenement and walked into a room thick with cigarette smoke and full of drunk people. The paramedics recognized one of the bystanders as a prostitute they had encountered on previous occasions. She directed the paramedics to the bathroom, where they found a 35-year-old male draped over the toilet.

The prostitute said, "He's been drinking whiskey all day, he's been throwing up for the last hour, and I want you to get him outta the bathroom because I need to use it.”

One of the paramedics asked the patient, "What's going on?'' to which the patient responded with an obscenity.

The paramedic said, "You seem sick. Is anything bothering you?''

He mumbled something that sounded like "chest pain."

Pulling the patient out of the bathroom, which was too cramped, the paramedics started their physical evaluation. The patient was awake, incoherent and uncooperative. He smelled strongly of alcohol, vomit and urine. He seemed very weak, his skin was cold and mildly diaphoretic, and his conjunctivae were pale.

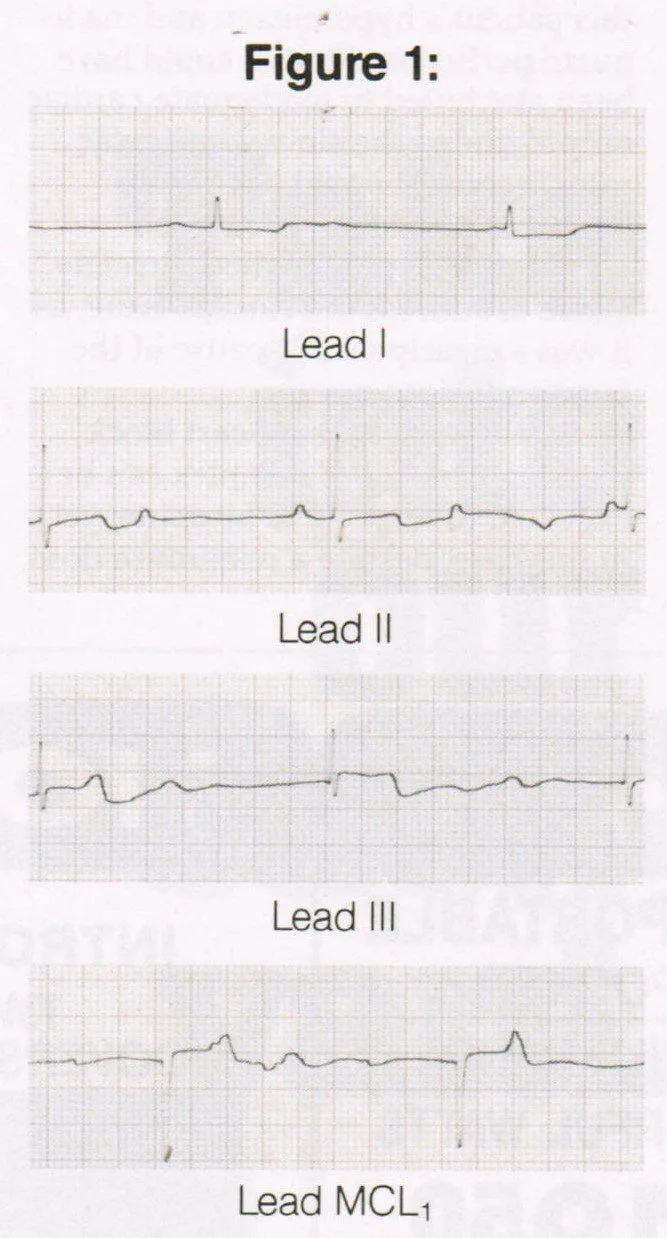

Although the paramedics were unable to palpate radial or brachial pulses, they thought they could feel a weak, slow carotid pulse. (It was, however, too weak to count with confidence.) Blood pressure was unobtainable and respirations were 28 per minute. His EKG at this point is shown in Figure 1. (Leads I, II, III, and MCL1)

After identifying his electrocardiographic rhythm as complete heart block with narrow QRS complexes, they started an intravenous line (D5W TKO) and oxygen by non-rebreather mask at 12 1/min. He was given 0.5 mg atropine IV push, with no response. The atropine was continued in 0.5 mg increments to a total dose of 2 mg, with the only perceptible change being the dilation of the patient's pupils. There was no effect on heart rate, strength of pulse or blood pressure.

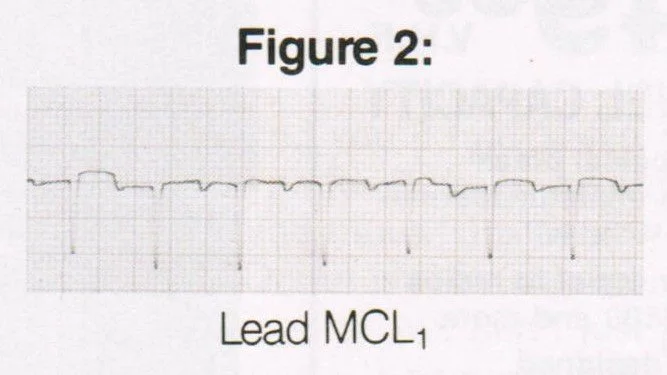

The patient was then evacuated to the ambulance where contact was made with the base-station physician. (Total on-scene time was about 15 minutes.) The decision was made to hang an epinephrine drip. After 60 seconds of epinephrine infusion, the patient's pulse became strong and mentation improved to a level where the patient became combative. During transport, his blood pressure increased to 140/90. His EKG at this point in transport is shown in Figure 2.

The patient was restrained with soft Kerlex restraints and given Narcan and D50. Although the patient was awake, he was not alert or oriented, a state which persisted despite these two medications.

In the emergency department, each time the physicians tried to slow down the epinephrine infusion, the patient's complete heart block returned, along with a state of poor perfusion. A transdermal pacemaker was placed on the patient, and the epinephrine drip was slowed until the pacemaker took over. The patient required IV Valium and Haldol to manage his combativeness and to make the discomfort of external pacing more tolerable.

Once the pacemaker captured well, the epinephrine drip was discontinued. The patient was then taken to the cardiac catheterization lab for placement of a transvenous pacemaker.

The next day, while in the cardiac care unit, the patient admitted to smoking six "rocks" of crack just prior to the episode.

Case Discussion

The paramedics were astute in their rapid evaluation that this was not "just a drunk.” Rather, he was quickly recognized as a critically ill cardiac patient with signs of grossly inadequate perfusion. Immediate intervention was essential and was provided to him, despite the gut-wrenching aroma and less than pristine atmosphere.

The most striking aspect of the initial electrocardiogram was the slow ventricular rate of about 30 beats per minute. That, in addition to the independent atrial activity in the absence of capture beats, lead to recognition of complete heart block. The axis was normal (upright QRS complexes in leads I, II, and III). Because the QRS complexes are narrow, this is a junctional escape rhythm, which is sometimes referred to as a proximal complete heart block.

Pertinent Points

There are two probable reasons for this patient's hypotension and inadequate perfusion. First, it could have been attributed to inadequate cardiac output due to the slow ventricular rate. Second, it could have been hypovolemia due to protracted vomiting. The paramedics correctly chose to address the cardiac issue, as it was a clearly visible cause of the hypoperfusion.

Usually, a complete heart block with a narrow QRS complex can be expected to respond to atropine; yet in this case, despite a maximum dose, the patient's perfusion was unaffected. As a parasympathetic blocker, atropine usually increases heart rate in areas of the heart innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system. Since the AV node is innervated by the parasympathetic nervous system and narrow QRS complexes are thought to originate there, it was unusual that atropine had no effect on this patient's heart rate.

The choice of an epinephrine drip vs. an Isuprel drip is becoming increasingly popular. An epinephrine drip is made by mixing 1 mg of 1:10,000 strength epinephrine in a 250 cc bag of D5W.

Isuprel and epinephrine both stimulate the beta-1 receptors in the heart and increase heart rate regardless of the anatomic origin of the QRS complex. Unlike atropine (which only affects the SA and AV nodes), both Isuprel and epinephrine have effects on the SA node, the AV node and the ventricles.

However, Isuprel also stimulates beta-2 receptors in the peripheral vasculature, causing dilation of the systemic circulatory system. In order to increase blood pressure (and consequently perfusion), adequate peripheral resistance is needed in concert with good blood volume and cardiac output. Therefore, in order for Isuprel to raise blood pressure and perfusion, it must compensate for the decrease in peripheral vascular resistance it causes by increasing heart rate accordingly. In other words, Isuprel "robs Peter to pay Paul.”

On the other hand, epinephrine not only stimulates beta-l receptors in the heart, but also stimulates the alpha receptors in the peripheral vasculature. This causes constriction in the systemic circulation – thus raising blood pressure and perfusion from two angles without sabotaging its own actions. In the end, because it requires less of an increase in heart rate and myocardial demand than does Isuprel, the increase in perfusion generated by epinephrine theoretically takes less of a toll on the alreadydamaged heart muscle.

Why, in a patient with a slow pulse and no palpable blood pressure, was an IV of D5W used instead of volume expanders? This is a debatable issue; there are sound arguments for both approaches in patients whose decreased perfusion may have multiple contributors.

In support of D5W, the most overt cause of diminished perfusion with a slow pulse (which is complete heart block) should be treated first. The other contributor for poor perfusion, in this case volume depletion from vomiting, is a comparatively benign (and objectively unmeasurable) possibility. Fluid overload of a sick heart can be injurious.

At any rate, in a case like this, it is a good idea to use an IV extension tube and a large-bore IV catheter. This gives the paramedic and subsequent caretakers the option to switch quickly to volume replacement fluids without having to fuss with the taped site.

This rhythm is diagnosed as a complete heart block, not "third degree heart block'' in accordance with the reclassification of AV blocks as described by Marriot. Reclassification eliminated ''degrees'' in describing heart block, for good reasons (See Cardiology Practicum, March, 1988, p. 45).

The best management tool for this patient's bradycardia was the transdermal pacemaker used in the emergency department. It is, however, no longer a technology limited to use in the ED. There are several prehospital systems in the United States that are already using transdermal pacemakers as part of their available arsenal of care.

Finally, smoking crack is bad for the heart! Crack, a form of cocaine processed so that it can be smoked, has a massive impact on the cardiopulmonary system. More and more, otherwise healthy young people are developing serious cardiac problems secondary to the recreational drug. As was true in this case, patients may be reluctant to share illegal relevant history and may be less than cooperative with paramedic attempts to assist. As always, don't let environmental (especially olfactory) distractions impede your search for underlying pathology.

References

1. H.J.L. Marriot, Practical Electrocardiography, 7th edition (Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins, 1983), pp. 340-50.